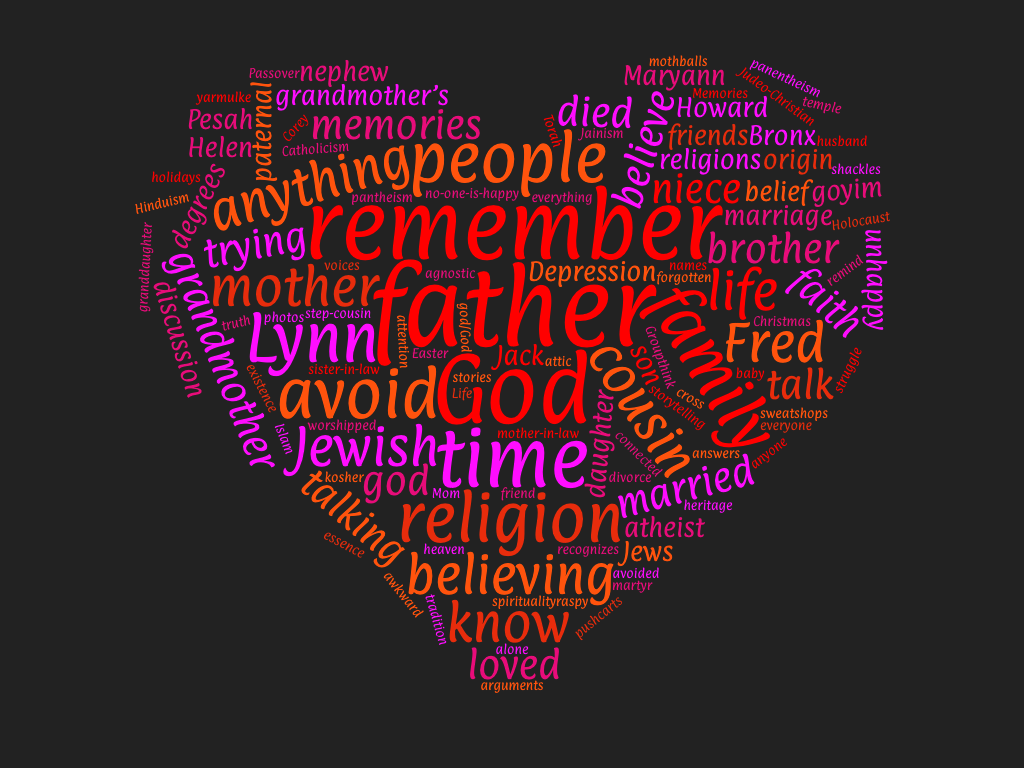

There is a very short list of things I avoid with Big Edie– they just lead to pointless, never-ending, no-one-is-happy circles.

There is a very short list of things I avoid with Big Edie– they just lead to pointless, never-ending, no-one-is-happy circles.

God.

It’s a safe to say the closer most people get to death, the closer they want to be to god/God. They start looking toward a god, a heaven, a life after, something that will provide answers, forgiveness, or relief.

Ours was one of those uniquely Jewish households where no one went to temple, wore a yarmulke, kept kosher, or did anything vaguely Hebraic outside of the way we spoke (with typical greenhorn sentence construction leaving the subject for last: That’s pretty, the dress), eating traditional food—but only on the big holidays that involved lots of cooking and eating, like Pesah Passover (we were not Jewish enough to actually use the word Pesah in a sentence) where the goyim at the table invariably outnumbered the Jews), and we did not fast. Ever. We went to confirmations and communions, Christmas and Easter dinners, eating with, and still outnumbered by, the same goyim, proving that you need neither God nor the Torah to still call yourself a Jew. Being Jewish was bigger than religion. It’s more than an ethnicity. It was the essence of our being, our heritage. It was Delancey Street pushcarts and the Depression, the Holocaust, the pogroms, and the “boat” that everyone came over on. It was not being able to trace our family any further back than the Bronx.

My parents were atheistic / agnostic Jews of Bronx descent. I don’t remember who started as what, but there was no God in our house. We kept tradition, not religion. Although they encouraged my study of mythology (Greek & Roman) and religion (Catholicism, Hinduism, Jainism, Judaism, Islam & on & on). Everything we needed could be found in a series of Life magazines (circa 1955) dedicated to the world religions that were safely stored in the attic, along with our heavy winter wool blankets and anything else we didn’t know what to do with. The fragrance of my childhood is camphor and eucalyptus –Vicks VapoRub and mothballs.

God, in our house, was a man-made construct. They tried Ethical Culture briefly. Any version of groupthink was the enemy of freedom, a tool of the oppressor, shackles of the masses.

The older she gets, the more rabid an atheist she is, declaring belief in God(s) and/or organized religion the source of all the world’s pain and suffering.

“Intelligent people agree with me,” she says, pointing to the stack of newsletters (I she’s on every atheist mailing list there is) and books (when she could still read) on her night table.

We agree on organized religion, but not about God.

She is flabbergasted, but not speechless.

“You’re smart. Too smart. How can you possibly believe in God?” Do I really believe in some invisible man in the sky who makes things happen? What about wars? Famine? She has all the usual arguments against the belief in a loving god. I’ve described where I see god (small g), the difference between religion and spirituality, my struggle to understand the fine points of pantheism and panentheism, how finding faith changed my life.

Almost by definition, you can’t argue with faith.

She gives it her best shot, anyway.

It’s exhausting.

A dozen years ago, we could have had a discussion, but her disease has progressed so she cannot grasp anything more nuanced than the cinematic Charlton Heston-ish Judeo-Christian version of God (capital G) and she vehemently denies “his” existence.

I avoid mentioning God or faith as much as I can. I use an old technique of hers for stopping situations and avoiding discussion she’d taught me in the hopes I’d use it with boys who pressured me to go further than I wanted to. “Just say no, and if they ask why, say: Because. That’s it. No matter he says, it’s no & because I don’t want to. If you don’t engage, you can’t get talked into, or out of (waving her long fingers at my clothes) something.” Non-engagement works in general, and because she can’t remember teaching it to me, it works on her as well. It’s a win-win, this not trying to talk each other into or out of (waving my stubby fingers around in the air) believing in God/god. She gets as much comfort from knowing for certain there is no God that I get from knowing there is.

Fred

Big Edie can’t remember names, friends or the path of familial connections. I find myself having to explain who someone is, why they’re calling, who they were to each other, what exactly a “niece” is, why they care about her, and why she should care about them. Simple family of origin connections are the easiest:

1. Your brother was Howard (I miss him/ I know, Ma),

2. Howard’s oldest daughter is your niece, Maryann.

Two degrees of separation. We get that far most of the time; things get fuzzier with each additional degree:

- Howard is your brother (He died too young / I know, Ma),

- Howard’s daughter is your niece, Maryann,

- Maryann’s son is your grand nephew, Corey,

- Corey’s son is your great grand nephew, Luca.

There’s just too much going on there. Anything beyond three degrees of anything is just poking the bear. By the time I get to the end, she’s forgotten the beginning. In this case, by the time we get to that baby, we have to circle back and start again with her brother. And over and over, it’s a virtual Escher staircase.

Considering that was the easy family-of-origin map, you understand why, besides their colossally lousy marriage, I try to avoid talking about my father, Fred. But sometimes I have to. Perhaps the top of this very short list of verboten subjects should’ve been my father, and therefore, anyone or anything that requires referencing him to explain them.

Mom recognizes the voices of people she loves, who love her, but that’s as far as that goes. Lynn called every Sunday and her distinctly raspy voice always ticked the right box in Mom’s brain: loved. They talked every week, and when the call was over, she’d turn and ask, “Who was that?”

“That” was my step-cousin, the granddaughter of my paternal grandmother’s second husband, Jack. To explain who Jack is, I have to remind her of Helen, her mother-in-law, which brings us back to my father, who she doesn’t remember, so there is not even a foundation to build on. We invariably make a sharp left turn as she wants to know stories about my father, tries to understand how her husband and my father were the same person, and tries to remember the man she was married to until he died. And Lynn? Well, we were never going to be able to circle back there once we’ve gone off on the who-was-Fred tangent.

They were married for forty-five years. Looking at photos, she remarks either on how good she looked or how handsome he was. They were a good-looking couple.

Memories are sporadic, and they’re only the bad ones. He was mean to his mother. And other people. And her. She has a hard time believing she didn’t divorce him, that she stayed until the death-do-us-part part. So did I, at the time.

She couldn’t see that there had always been a way to leave, that staying is always a choice. Comfortable as a victim and a martyr rooting for the underdog, she’d take his mother’s side & made things worse for everyone. She took my side & made things worse for everyone. She took her friend’s side & made things worse for everyone.

Their good times happened when no one else was around. All he ever wanted was her, and her undivided attention, loyalty, and time. Unfortunately, she needed people.

She “couldn’t” leave because:

Reason #1: Him

Before they even married, she knew he was a hustler and a liar, equipped with less than the standard set of morals most of us are born with. Still, she believed he couldn’t survive without her (Get off the cross, Ma, we need the wood!). Maybe she was right. Maybe not. Later in life, he had health issues, lacked salable skills, and had always had a basically shifty nature. He was able to justify giving up even trying to hold down a job. She never stopped working or supporting the family. My mother was my role model in many ways: the way women are strong and need never depend on a man for survival. Unfortunately, it’s also where, I learned to equate being needed with being loved.

Reason #2: Me

She didn’t want me growing without a father the way she had. Her mother had divorced and raised two children alone during the Depression, working in sweatshops and forced to take in boarders.

What I’m saying is, it’s not always pleasant, but there is always a way out.

Maybe staying was self-protection. She’s blamed him for everything she thinks went wrong in my life (drugs, alcoholism, sex work, lack of focus, lack of life partner, childless). If she’d acknowledged a way out, she’d have to take some responsibility for those wrong turns as well.

“You have good memories of your father?” she asks. I do, I say. She shakes her head. “But, you stayed away from home because of him. You ran away.”

From my child’s-eye-view, I saw two good-looking, unhappy and mis-matched Bronx-bred Jews (a mixed martyr/bully marriage at that) who should never have married each other. Nobodies fault. Or maybe fault lines in shitty marriages between unhappy people trace so far back it’s irrelevant. Maybe it just wasn’t the best place to raise a kid.

How do I explain I was equal parts terrified of, hero-worshipped, and loved a man she can’t remember, but is sure she divorced when she does remember anything. To explain any part of my father’s side of the family, to talk about childhood family memories, my grandmother, cousins, half the makeup of who I am today, I have to let her make him the bad guy.

It took me years for the love and compassion part of that equation to outweigh the terrified child. I can’t fit all of that into the few moments as I hand her the phone when Lynn calls. The best I can do is just say, “You’ll recognize her voice,” and hope for the best.

Discover more from only the jodi

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Whew. It can be hard to leave, it can be hard to stay. I think you got it right though, in the end what really matters is compassion.

Big Edie not believing in God and you believing in god was an unexpected twist! I love the breakdown of how you explain who Maryann is, and how you get to Luca. Your life is so rich. And I love that you’re writing it all down.