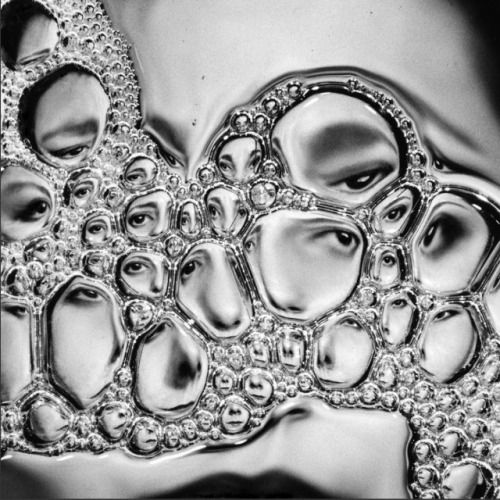

When I don’t know where I’m going, it’s best to start, not at the beginning, but where I am. Except, for someone with dementia or caregiving for a loved one with dementia, where you are is a moving target. I have a dozen unfinished posts because everything changes–quickly–then turns back, makes a left, heads down the road a piece, takes a u-ey, does a donut, skids off the road, then back on track. Then not.

That’s our life. One of our brains is driving drunk. The other is in the passenger seat, along for the ride. Neither of us can reach the brake pedal.

Laying side-by-side watching an episode of Everybody Loves Raymond (at least the 50th time I’d seen it, whichever one is was. I know the dialogue & timing of every episode and can name that plot-line within a minute of the opening – where is that category on Jeopardy? Or Who Wants to be a Millionaire? But, it’s new to her every time.), she turns and says, “I love you.” A minute later, “What is your name?”

What she knows, can do, wants or feels changes constantly and inconsistently.I imagine it’s like living in a snow globe. Things settle, then get shook up, over and over. You can never put all the pieces together, you grab two with this hand, and one floats out of your other hand. Imagine trying to reassemble the lettuce in a chopped salad.

Sometimes she knows that she isn’t who she was, can’t do the things she once did, like Suduko, Gin Rummy, or putting on her bra. Yesterday, she called me into the bathroom. She needed more toilet paper to wipe her bum with. There was a full roll in front of her, and two or three sheets in her hand. For that moment, she didn’t know how she got those two or three sheets of double-ply, but knew enough to ask for more. She almost always remembers my name when help is needed.

I cleaned her up with the disposable “adult” wipes, and if she was a little embarrassed, she forgot within a minute of saying “You’re so good.”

Who I am is fluid. I’m her daughter, but there are a lot of Jodis of all different ages. “Jodi” has morphed into a pronoun for child/children. I am an only, but to accept that she’d have to let go of all her other Jodis: the infant, the toddler, the teen.

I am also her son.

Again, I’m an only child. And admittedly, I am not the most girly girl of girls, but my pronouns are she/her/hers and I do not now, nor have I ever had a penis of my own.

I am her brother, her husband, her lover, an old friend, a new friend she met today. I am the father who walked out when she was a child. The mother she misses terribly who gave her the blanket (that I made), bought her the wheelchair she uses (yes, me again), who hasn’t called since she helped her moved in to “this place.” Grandma died when I was 13. Mom was 40.

I am a moving target. Not for her, but for myself.

When I walk into a room who am I supposed to be? What will be expected? I worry about what I will do that day I frighten her during the day. Right now, even though she doesn’t always know who I am, I’m safety. I’m comfort. Security. Shelter, food, and warmth.

I’ve seen the flip side during her nightmares. They’re not new, but she gets stuck in them now, dementia erasing the line between waking and sleeping lives. I try to wake her when she’s screaming or struggling in her sleep, to bring her back, but she’s stuck. Her fright manifests as anger, as it does with possibly most of the world. She orders me out of the room. I know what you’re trying to do. You and my husband are working against me. Get out. Don’t touch me. I know who you are.

She talks in her sleep. To me. To friends. To the group. The group is also a moving target. They having those nothing special conversations, the easy way you do with friends. That shirt looks nice on you. Did you have lunch? Where are you going? Hello, I’m talking to you, pay attention. They make plans to have dinner, go to the movies, visit each other. A robust life with unnamed friends and family. When she wakes they’re gone, but not forgotten. The dream life is remembered vividly. Doctors appointments. New apartments. Evictions. Boyfriends. Family.

Sometimes, later in the day, fully awake but tired or upset or during the sundowning, her words are gibberish. Sometimes she grabs for a word and gets the first letter right, or the image. Pillows mean teeth. Also pain. Also, sometimes a pillow is just a pillow. Imagery and first letter. Cards are cars, any kind of paper, any way of communicating, reading material, recipes, money. “Cards” are the default word when she can’t grab one, it can be a dozen different things. Reminder to self: Replace “Wanna play cards?” with “Wanna play 500 Rummy?” But, sleeping seems to temporarily suspend the aphasia and there is no struggle with language. Her life–asleep–is inordinately better than her life awake. Friends. A cat curled into her arms. A comfortable bed. Good music. Who can blame her for wanting to sleep all day?

Sleep, timing, and the right medications can create a pleasant day for everyone. Which medications are “right” changes as the disease progresses, as her health and needs change. In this moment:

- Miralax and prune juice keep things moving

- Memanitine & Donezipil, our thin hopes of slowing down the progression of the disease, the theft of my mother’s mind

- Antidepressants keep depression to a minimum and usually corralled to the period of sundowning

- Seroquel, an anti-psychotic normally prescribed for schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, gives a little zetz to the antidepressants and keeps anxiety at a minimum. Neither bipolar nor psychotic, Ma’s dose can focus on visible and invisible anxiety.

Anxiety is the new normal when your reality changes minute to minute. Where do I live? Who else sleeps in this bed? I don’t like apple cider. Is my mother alive? Where did everyone go? I have to get dressed for school/work. Who are you? This is delicious, it’s apple cider? Morning/ Day/ Evening/ Night. I cannot read my watch anymore. I have surgery tomorrow, something’s bad & they have to remove everything. I can’t walk very far. I can walk. I need someone to push me in the chair, I can’t walk at all. I’m afraid of driving. I drive all the time. I’m not going to any doctors. I have a pain in my back, teeth, ear, hair, belly, breasts. What are you asking, I feel fine.

How do you play a game when the rules keep changing and everyone has a different set of instructions? How do I?

Stay in the moment.

Know your medications and the disease.

Work backwards to create a schedule.

Be wily.

Improvise.

- Seroquel makes her sleepy ninety minutes after taking it, and allays anxiety for about six hours.

- Sundowning (aka each evening’s burst of fresh anxiety and confusion) starts around 4:30 pm. Six hours before that would be 10:30, but you want some overlap.

- 11:00 am Seroquel means a 12:30 two-hour nap.

- 4:30 pm Seroquel (one-hour overlap) means drowsy hits at about 6:00 pm, so dinner should be finished before 6:00 pm.

- If she is in bed by 7:00 or 8:00 pm to watch television (Family Feud, Everybody Loves Raymond, The Good Place), she will be asleep by 9:00 or 10:00 pm–an average of twelve to thirteen hours sleep a night, plus a two-hour nap.

That’s fourteen hours out of twenty-four she can spend with “her group” in a world where she is clear-headed and in command of her body, her mind and her language.

If there’s a heaven, you’ll get there!

Ha! I don’t know about that. The years from age 13-33 we refer to as Jodi’s lost years…

33-40 weren’t that much to write home about either. But that all was an entirely different blog.